The following terms are used by victim advocates, service providers, policymakers, researchers, and academics working at the intersection of trauma and domestic violence. Being familiar with the meaning of these terms will deepen your understanding of the field and make it easier to communicate with others about trauma and trauma-informed services.

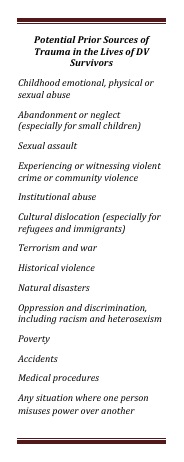

1. Individual Trauma. Trauma is the unique individual experience of an event or enduring condition in which the individual experiences a threat to life or to her or his psychic or bodily integrity, and experiences intense fear, helplessness, or horror. A key aspect of what makes something traumatic is that the individual’s coping capacity and/or ability to integrate their emotional experience is overwhelmed. Trauma often impacts individuals in multiple domains, including physical, social, emotional, and/or spiritual (Giller, 1999; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995;van der Kolk & Courtois, 2005).

1. Individual Trauma. Trauma is the unique individual experience of an event or enduring condition in which the individual experiences a threat to life or to her or his psychic or bodily integrity, and experiences intense fear, helplessness, or horror. A key aspect of what makes something traumatic is that the individual’s coping capacity and/or ability to integrate their emotional experience is overwhelmed. Trauma often impacts individuals in multiple domains, including physical, social, emotional, and/or spiritual (Giller, 1999; Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995;van der Kolk & Courtois, 2005).

2. Collective, Organizational, and Community Trauma. The terms collective trauma, organizational trauma, and community trauma refer to the impact that traumatic events can have on the functioning and culture of a group, organization, or entire community (e.g., the effects of the 1999 Columbine High School shooting, Hurricane Katrina, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks on their respective communities).

3. Historical Trauma. Historical trauma refers to cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experiences. Understanding historical trauma means recognizing that people may carry deep wounds from things that happened to a group with which they identify, even if they did not directly experience the event themselves. Historical trauma follows from events such as the colonization of generations of Indigenous Peoples, the enslavement of Africans and their descendants, and the losses and outrages of the Holocaust. While the term refers to events that occurred in the past, it is important to remember that for many communities the trauma or oppressive conditions associated with the historical trauma have been institutionalized and are ongoing (Packard, 2012; BigFoot, 2000; Willmon-Haque & BigFoot, 2008, Braveheart, 1999).

4. Intergenerational Trauma. Intergenerational trauma refers to the effects of harms that have been carried over in some form from one generation to the next. The concept is similar to historical trauma, although it is frequently used to refer to trauma that occurs within families rather than in larger (e.g., racial, ethnic, cultural, or religious) groups.

5. Insidious Trauma. Insidious trauma refers to the daily incidents of marginalization, objectification, dehumanization, intimidation, et cetera that are experienced by members of groups targeted by racism, heterosexism, ageism, ableism, sexism, and other forms of oppression, and groups impacted by poverty. Maria Root, who coined the term insidious trauma described the concepts as follows:"Traumatogenic effects of oppression that are not necessarily overtly violent or threatening to bodily well-being at the given moment but that do violence to the soul and spirit. " (Root 1992; Brown & Ballou, 1992)

6. Trauma-Informed. A trauma-informed program, organization, system, or community is one that incorporates an understanding of the pervasiveness of trauma and its impact into every aspect of its practice or programs. In such settings, understanding about trauma is reflected in the knowledge, attitudes, and skills of individuals as well as in organizational structures such as policies, procedures, language, and supports for staff. This includes attending to culturally specific experiences of trauma and providing culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate services. It also includes recognizing that not only are the people being served potentially affected by trauma but that staff members may be as well.

Central to this perspective is viewing trauma-related responses from the vantage point of "what happened to you" rather than "what’s wrong with you," recognizing these responses as survival strategies, and focusing on survivors’ individual and collective strengths. Trauma-informed programs are welcoming and inclusive and based on principles of respect, dignity, inclusiveness, trustworthiness, empowerment, choice, connection, and hope. They are designed to attend to both physical and emotional safety, to avoid retraumatizing those who seek assistance, to support healing and recovery, and to facilitate meaningful participation of survivors in the design, implementation, and evaluation of services. Supervision and support for staff to safely reflect on and attend to their own responses and to learn and grow from their experiences is another critical aspect of trauma-informed work.

The term trauma-informed services was originally coined by Maxine Harris and Roger Fallot in their edited book, Using Trauma Theory to Design Service Systems (2001) and has been adapted by multiple writers and in multiple service settings. This working definition by NCDVTMH is adapted specifically for the DV field and incorporates some of the original elements as well as other elements and concepts critical to our work with survivors.

7. Trauma-Specific. The term trauma-specific refers to interventions or treatments designed to facilitate recovery from the effects of trauma. There are a number of promising and evidence-based treatment modalities that address PTSD and other trauma-related conditions (e.g. depression, substance abuse, complex PTSD), although few have been designed specifically for domestic violence survivors. Trauma-specific services, while intended to address the consequences of trauma, may not always be trauma-informed. In other words, they may focus on treating trauma symptoms without necessarily being attuned to the experience of trauma or ways the service setting and processes may themselves be retraumatizing (Harris & Fallot, 2001; Warshaw, Brashler & Gill, 2009; Warshaw, Sullivan & Rivera, 2012).

8. Triggering. A trigger is something that evokes a memory of past traumatizing events including the feelings and sensations associated with those experiences. Encountering such triggers may cause us to feel uneasy or afraid, although we may not always realize why we feel that way. A trigger can make us feel as if we are reliving a traumatic experience and can elicit a fight, flight or freeze response. Many things can be a possible trigger for someone. A person might be triggered by a particular color of clothing, by the smell of a certain food, or the time of year. Internal sensations can be triggers, as well. Once we become aware of triggers, we might feel an impulse to "get rid of all possible triggers. " Of course, we will avoid violent images or angry tones in our speech and try to make the environment calm. However, there will always be trauma triggers that we cannot anticipate and cannot avoid. Part of trauma-informed work is supporting survivors as they develop the skills to manage trauma responses both in our service settings and elsewhere in the world (National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health).

9. Retraumatization. Retraumatization occurs when any situation, interaction, or environmental factor is itself traumatic or oppressive in a way that also replicates events or dynamics of prior traumas and evokes feelings and reactions associated with the original traumatic experiences. Retraumatization may compound the impact of the original experience.

10. Revictimization. Experiencing abuse—including physical or sexual abuse or sexual assault—increases our risk of experiencing violence or abuse in the future. Revictimization may occur in a similar or different context. When examining the prevalence of revictimization, it is important to consider the social context and the factors that put people at greater risk for being victimized (Kimerling, Alvarez, Pavao, Kaminski, & Baumrind, 2007; Lindhorst & Oxford, 2008; Classen, Palesh, Aggarwa,l 2005).

11. Secondary Traumatic Stress (Vicarious Trauma). Secondary traumatic stress (sometimes called vicarious trauma) refers to the emotional effects that can occur when an individual bears witness to the trauma experiences of another. For example, DV victim advocates may experience secondary traumatic stress from listening empathically to survivors recounting their stories. Individuals affected by secondary traumatic stress may themselves experience trauma-related responses as a result of the indirect trauma exposure or may find themselves re-experiencing trauma that they have experienced in their own lives. The cumulative effects of secondary traumatic stress may be seen in both professional and personal life.

12. Compassion Fatigue. Compassion fatigue is a related term used to describe exhaustion and desensitization to violent and traumatic events encountered in professional work or in the media. Both secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue can result from bearing witness and connecting empathically to another person’s experience and being emotionally present in the face of intense pain (Pearlman and Saakvitne, 1995; Prescott, personal communication, 2005).

13. Resilience. Resiliency is our inherent capacity to make adaptations that result in positive outcomes in spite of serious threats or adverse circumstances. Experience working with survivors and research on resiliency show that there are some factors that appear to support and enhance our resiliency. Having a supportive community, whether through one's family, neighborhood, school, church, sports activities, or hobbies, is one factor that supports resiliency. A feeling of being valued and belonging is important, as well as being able to engage other people in positive ways, whether through one’s ability to relate to others or through one’s capacities and talents. For children, factors that support resiliency include the response of caregivers and other caring adults, namely having at least one person who takes an interest in the child and their development, sees them as a separate person, and helps them develop their ability to cope (Masten, 2001; Masten, 2009;Masten & Wright, 2009).

14. Reflective Practice. The term reflective practice was coined by Donald Schon, who described it as "the capacity to reflect on action so as to engage in a process of continuous learning." In our day-to-day work, reflective practice involves a process of mutual and ongoing learning in an organization. As an approach to supervision, it removes the authoritarian "top-down" focus of some administrative supervision, replacing it with a collaborative approach that allows the knowledge, expertise, and experience of program staff to be shared, strengthened, and applied to our mutual goal of increasing safety and empowerment for battered women and their children. In individual DV work, the advocate approaches all her encounters with survivors with a readiness to examine her own practice and to reflect with and about the survivor's needs and experience in order to meet the survivor's goals (Schon, 1983).

15. Peer Support and the Peer Movement. Peer support is a way for people from diverse backgrounds who share experiences in common to come together to build relationships in which they share their strengths and support each other’s healing and growth. Peer support promotes healing through taking action and by building relationships among a community of equals. It is not about "helping" others in a hierarchical way but about learning from one another and building connections. Mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence all have strong traditions of peer support, although these traditions differ somewhat in their histories and their specific goals. In the mental health community, the peer movement is a term used to describe the political advocacy movement of people with mental health diagnoses who seek to increase their control over services and change laws limiting their rights (formerly called the consumer, ex-patient, or survivor movement). The peer support movement, however, does not focus on diagnoses but is rooted in compassion for oneself and others (Blanch, Filson, Penney, et al, 2012).